The Big Idea: A plan to save Mumbai

A real, executable template for a people’s city by PK Das, Principal, P K Das and Associates, Mumbai.

We see the movement to protect Mumbai’s seafront as not merely a beautification programme, but as part of a larger democratic struggle to reclaim public space, and to create spaces where people meet, share their experiences and begin to care about each other and garner social relationships.

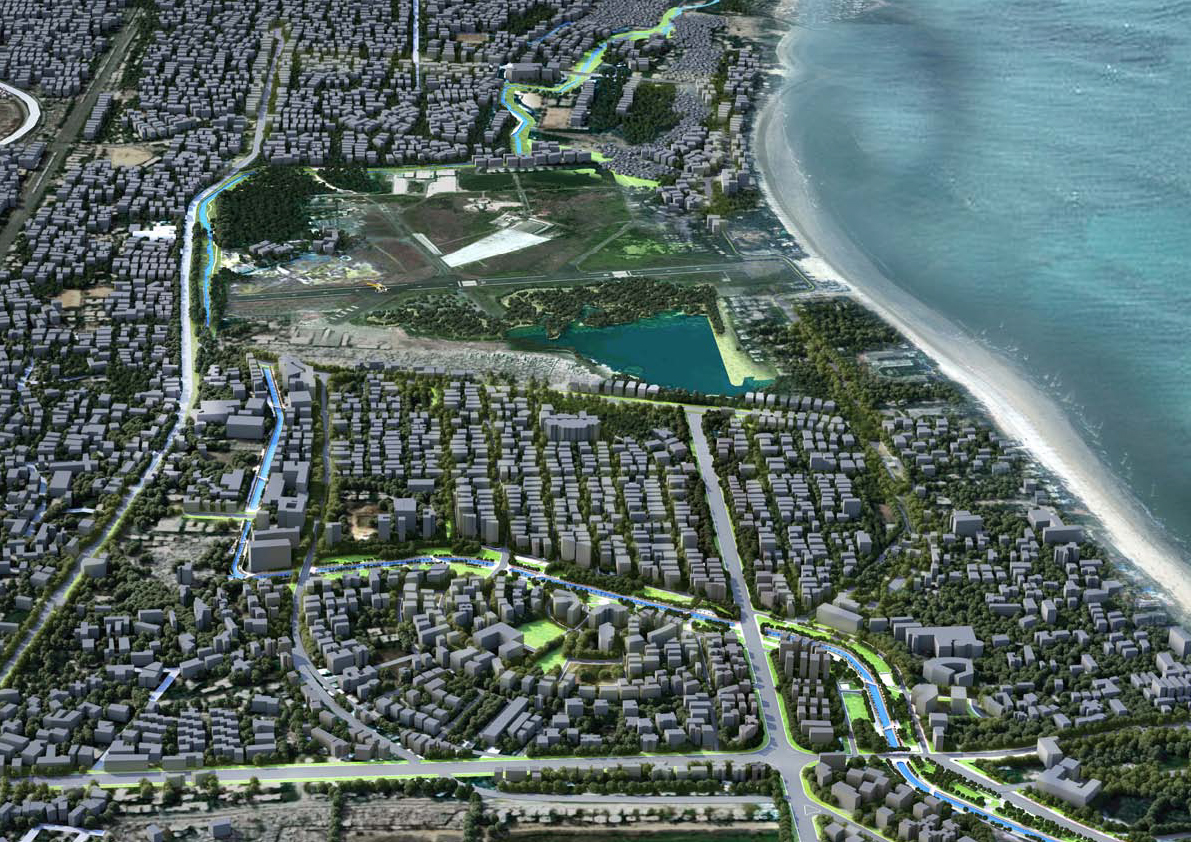

Mumbai is a city by the water with 140 sq km of natural assets: picturesque coastline, creeks, rivers, wetlands, beaches, mangroves, hills, forests and more. Sadly, the city has turned its back on these prize topographical features and considered them dumping grounds – both physically and metaphorically, leading to their rampant destruction and degradation. Reclamation, sewage disposal and encroachment have ravaged the waterfront.

As Mumbai expands, its open spaces are shrinking. Its people-to-open-space ratio is amongst the lowest, at a shabby one square meter per person. The democratic ‘space’ that ensures accountability and enables dissent is also shrinking; very subtly, but surely. The city’s shrinking open spaces are, of course, the most visible manifestation as they directly and adversely affect our very quality of life. Pollution, congestion and flooding, leading to human and economic loss, have risen to alarming levels.

While the eastern coast has been put to use for defense and docks, thus restricting public access, the city’s 34 km-western coast has never been considered in the planning and development process. But, for the millions who live in this crowded city, the waterfronts are the only major open spaces, whether it is Marine Drive, Chowpatty, Haji Ali, Worli Sea Face, Dadar Beach, Bandra Bandstand, Carter Road, Juhu Beach or Versova. Unplanned commercialization has destroyed the natural environment considerably. The absence of a master plan for the development of the waterfront has encouraged the rich and the powerful to manipulate and grab land along the coast, thus gradually depleting the city of its most vital open spaces.

Reclaiming waterfronts and expanding public spaces:

We aspire to transform how Mumbai’s institutions approach open space and provide equitable access to ecosystem services for millions. Our objectives have always been :

- to conserve the vital natural assets

- their integration with neighborhoods and the city

- expanding public spaces, both in physical and democratic terms

- expanding tree cover

- popularizing and de-mystifying the planning process for effective participation

- promoting the idea of neighborhood-based city planning

We offer simple, modest and pragmatic design solutions that work within the existing realities to solve key problems. This, we expect, will generate a momentum for positive change. There are no grandiose ideas here. In fact, no major construction should be allowed on these waterfronts. Second, we propose a selective reallocation of spaces and activities, and third, very minimal restructuring. Most importantly, these waterfronts must remain the collective asset of the city and all its citizens, and a vibrant element in its environmental and social fabric. In the redeveloped sections, a new relationship between the people and the public space emerges.

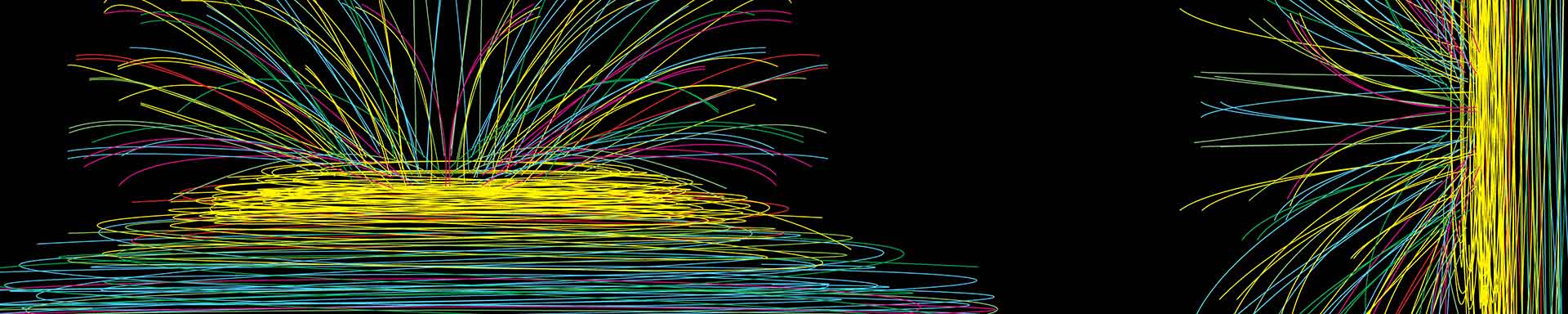

Traditionally, Mumbaikars have had little access to open space. Now, imagine access to 600 km of landscaped walking and cycling tracks, and open spaces along watercourses that interweave through various parts of the city’s urban fabric. This is the vision of our collective effort via the Irla Nullah Re-invigoration Project. The plan, which is a part of a larger citizens’ movement advocating the ‘Vision Juhu’ Plan, focuses on cleaning a polluted natural watercourse in the coastal suburb of Juhu and transforming it into a vibrant public space. Our movement is executed through the participation of local citizens, elected representatives, officials of the government, celebrities, educational and commercial institutions, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and certain state and national government agencies.

An extensive public communications campaign has led to wider participation in the project. Importantly, this project exemplifies the need to involve diverse stakeholders in the people’s ‘Right to the City’, and their role in scripting urban growth. This requires systemic change in city institutions and in how people participate in the democratic process. What was, for many years, a filthy backyard to the city and neighborhood has now been transformed into a forecourt for social and cultural activity. Neighborhood citizens’ associations, zealous maintenance activities and social events are all signs of a positive and socially participatory attitude that is emerging slowly.

The current mindset of planning has to be challenged too. Sustainable ecology and environment has to be the central aspect of city development plans, prepared with people’s participation. Our mission is to facilitate the rejuvenation and integration of open spaces, the natural areas and the wider city.

In Mumbai, most of the over-300 km of nullahs were originally natural watercourses, or rivers. Connected to the sea and thereby the tides, these water bodies regulated ground water level and assisted in dispersing water from the land in case of intense rain. These watercourses have unfortunately been abused – becoming open sewage drains, which take our effluents out into the sea. People living in Mumbai generally associate nullahs with dirt, filth and odor. Over the years, public knowledge of them as rivers and natural watercourses that defined the landscape has been lost. Sadly, the city government has channelized these water bodies by building impervious concrete walls along their edges, thus further severing their ecological and environmental attributes, and separating them from the people.

Can we re-envision our city with streams of open spaces and water, defining a new geography? Can we restore these nullahs to their past glory, and contribute towards the ecological regeneration of these natural assets? Can we simultaneously break away from large monolithic spaces and geometric structures of parks and gardens into fluid streams of linear open spaces meandering, modulating and negotiating varying city terrains? Can we re-design nullahs to be linear parks? This way a new structure of open spaces and watercourses would relate to and integrate with many more areas and people across neighborhoods and the city. These are some of the ideas that the Irla Nullah Re-invigoration Project evokes.